The Fawn Response Explained

Do you find yourself putting everyone else's needs before your own?

Understanding the Fawn Response: When People-Pleasing Becomes a Survival Strategy

Do you find yourself almost automatically becoming subservient to others? If yes, you might have the fawn response.

What is the Fawn Response?

The fawn response is a people-pleasing behavior where you prioritize other people's needs over your own, often at significant self-sacrifice. You might even prioritize their wants over your own needs. This happens so automatically that you're not even aware you're doing it until you're well into it.

The fawn response can be driven by:

- A real fear of conflict

- A desire to avoid any disapproval

- A desire to stay in relationship rather than take care of yourself

The Childhood Origins of Fawning

The fawn response usually develops in childhood when your caregivers are either neglectful or abusive. As a child, you are dependent on your caregivers to take care of you, so it is a real survival need to stay connected to them.

If you learn young that in order to stay connected, you have to squash your own needs, definitely squash your own desires and wants, and prioritize the other person's needs, wants, and probably emotions, then you learn this habit of fawning or people-pleasing in order to survive. The degree to which it's ingrained in your old brain is very, very strong. When things are embedded as a survival response, they can automatically dictate behavior for a long time until we learn how to change it.

Complex Trauma and the Fawn Response

The fawn response is most often related to complex childhood trauma where the traumatic events or the absence of connection are ongoing. Not necessarily a one-time trauma, but rather an ongoing theme and atmosphere of childhood.

In these situations, it's actually very adaptive for the child to learn to please — even excessively please and appease the caregiver. It's adaptive because it is needed for their survival.

Understanding Fawning Behavior

If you would like to understand your own fawning behavior, or if you are trying to understand somebody else who has habitual fawning behavior, it's important to recognize that fawning developed as a survival response to stay in relationship.

You'll see people talk about the fawn response and say things like "people who fawn try to create safety by staying in relationship" or that "they seek safety by merging with the other person's needs, desires, etc." While this is kind of true, I don't think that's phrased in a way that really resonates with the feeling of fawn behavior.

The real thing is that fawning developed when the safest choice was to stay in relationship, even if it was with somebody abusive. As a child, that was unfortunately the safest choice. So that urgency, that drive to fawn, that drive to people-please, feels like a total necessity.

The habitual pattern remains even when it is no longer a necessity. For most of us as adults, we need relationships to be happy and healthy, but the urgency to sacrifice your own values and needs is no longer required. If you're in a relationship that requires that, you probably don't need to maintain that relationship. This isn't easy, but it's important to begin to think about how that survival response is not needed today.

Fight, Flight, Freeze, and Fawn

You'll often see fawn talked about as a fourth "F" alongside fight, flight, and freeze. I actually think it's different, and this section explains why.

The fight-flight-freeze response is part of our reptilian brain. It is not about relationship. It doesn't tie into language centers. It's an automatic quick response to flee, fight, or freeze in the face of immediate danger.

People with the fawn response probably developed it from a freeze or a flight response. Most people with the fawn response are either "flee-ers" or "freezers," but the fawning actually utilizes higher-level cognition areas of the brain. It also utilizes the part of our autonomic nervous system which is about relationship and connection, which are not utilized by the amygdala.

Similar to the fight, flight, and freeze responses, fawning behaviors can be adaptive in certain situations. The problem with all four of these responses is when they are automatically applied in situations that don't require them.

If you are faced with immediate life-threatening danger and you can't flee and you can't fight, freeze can be the most adaptive response. Similarly, if you're in a situation where fawning will get you out of it, that can be the most adaptive choice.

Any one of these responses, if applied in a situation where it makes sense, can actually be helpful. What you don't want is an automatic response of fawning in situations where it's not needed — just as you wouldn't want an automatic response of freezing at a work meeting or starting a fist fight at work (an excessive fight response).

Breaking Free from the Fawn Response

So knowing that your fawn response developed to keep you in relationship and to keep you safe when you were a child helps you understand how this became ingrained as a habitual pattern, and helps you have more self-compassion. If it now feels automatic ain your relationships, you can understand that you are prioritizing connection and fearing any disconnection. This leads you to understand that you are fearing any conflict, and it begins to give you the ability to CHOOSE. As you begin to see this more clearly, and see where it came from, you can make a choose in the present day about whether or not you really want to sacrifice your relationship with yourself to maintain a relationship with the other. Healing is beginning to move these habits into the part of your brain where you can assess your choice.

Characteristics of People with a Habitual Fawn Response

People who have developed a habitual fawn response generally fear conflict and are very afraid of using any language that might be seen as aggressive.

When children grow up in a household with an abuser who uses very aggressive language, there might be one child who ends up mimicking that and that is the role they develop. And then the other child or the other children will avoid being in that role at all costs. They do not want to do anything that would make them seem like they were the abuser.

And then to add to that, being aggressive in an environment with somebody who is aggressively abusive puts you in more danger usually.

But a key here is that communication can be assertive, not passive and not aggressive. And finding that middle ground can be difficult, but it can be VERY helpful for someone with a habit of fawning.

Developing Assertive Communication

Assertive language is based on the principle: "I am okay, you are okay."

Passive is "You are okay, but I am not."

Aggressive is "I am okay and you are not."

If you keep that in mind, assertive language could be, "You do you, but I do not want to be around for it." This hints at some of the behaviors that will be developed as you heal, and those behaviors actually help you heal.

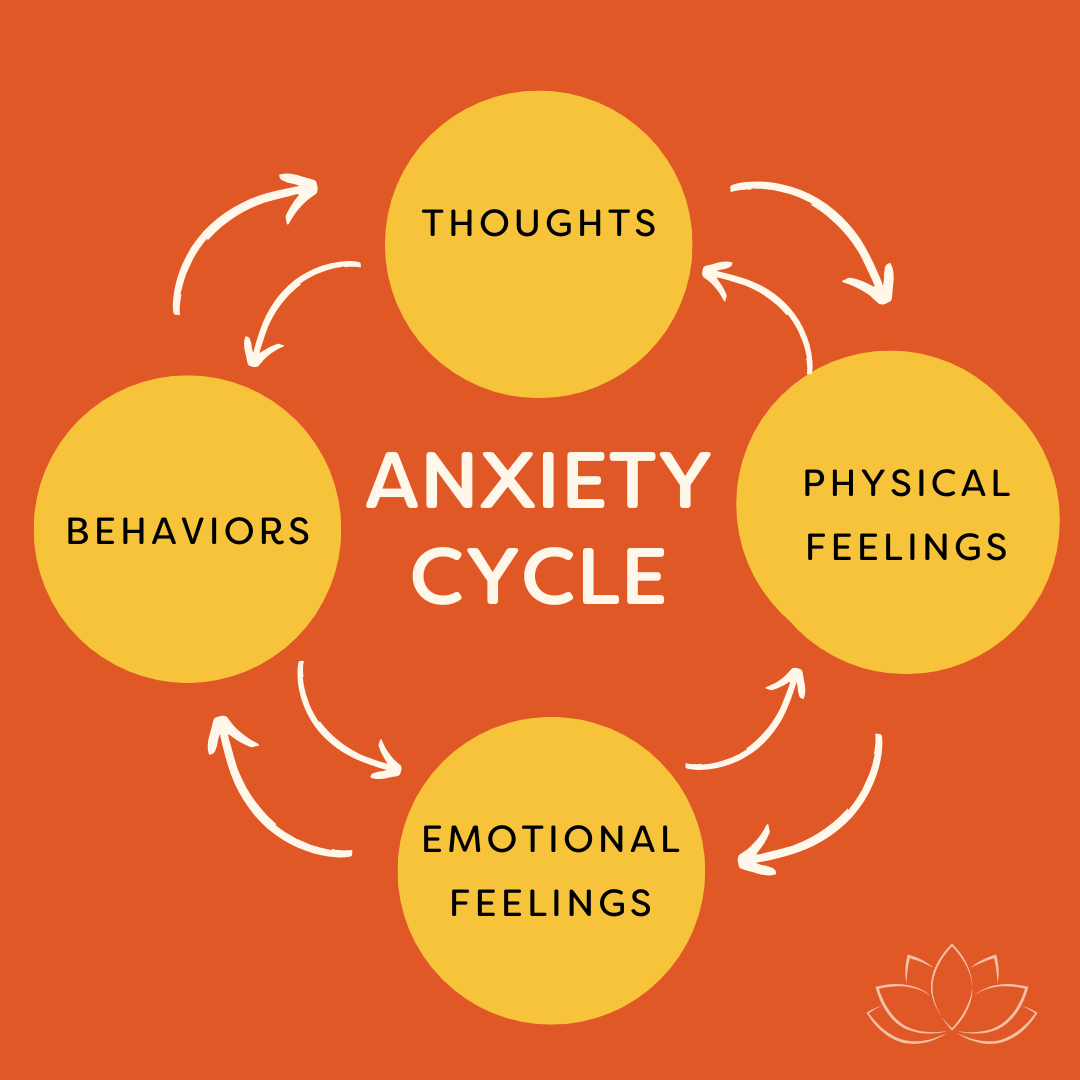

There is an effect where change in behavior impacts how we feel, and how we feel impacts our behavior. Changing some of these behaviors will improve your self-esteem, which will make it easier to change behaviors.

(I am going to talk about this more in my blog next week, so check back in!).

Also, my

online boundary program (click here for more info) has an entire section on assertive language. It provides examples and concepts so you can begin to utilize assertive language to take care of yourself and develop healthy boundaries.

Before you can improve boundaries, or change your fawning behaviors, you need to have strong emotional regulation tools. These are required to calm that fight, flight, freeze response, and thereby calm the fawning response. They also help strengthen the observer part of the brain which can help you analyze whether self-sacrifice is really needed or not.

Any questions, let me know. I look forward to seeing you next week.

Blog Author: Barbara Heffernan, LCSW, MBA. Barbara is a licensed psychotherapist and specialist in anxiety, trauma, and healthy boundaries. She had a private practice in Connecticut for twenty years before starting her popular YouTube channel designed to help people around the world live a more joyful life. Barbara has a BA from Yale University, an MBA from Columbia University and an MSW from SCSU. More info on Barbara can be found on her bio page.

Share this with someone who can benefit from this blog!